Gods in the House of Pain: Civilization and Savagery in Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau and Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

H.G. Wells’ early science fiction novels brim with invention but The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) is the most compelling read of the bunch, a dark masterpiece that takes a scalpel to the idea of the human and slowly tears it to shreds. I discussed in a post on Le Fanu’s “Green Tea” (1872) the operation of Darwin’s idea of evolution in horror fiction, and Wells takes Darwinian ideas relating to the kinship of man and beast even further and maximises their horrific implications in this novel.

The Island of Dr. Moreau is of the then popular genre of “found manuscript” stories (“Green Tea” is another such tale), and the manuscript that is found is the account by one Edward Prendick of his escape from the sinking of the Lady Vain in a dinghy, to be picked up and brought to an island where goings-on are of the strangest.

The real strangeness begins when Prendick comes to face to face with an inhabitant of the island:

He was, I could see, a misshapen man, short, broad, and clumsy, with a crooked back, a hairy neck, and a head sunk between his shoulders.

[…]

In some indefinable way the black face thus flashed upon me shocked me profoundly. It was a singularly deformed one. The facial part projected, forming something dimly suggestive of a muzzle, and the huge half-open mouth showed as big white teeth as I had ever seen in a human mouth.

Moreau, Chapter 3.

The hint of humanity in the apparently bestial is a theme of the book, disorienting the reader and prompting reflection on what makes humans human.

In the spectacularly dark and ahumanist apologia by the titular Dr. Moreau, he sees the gap as being far from insurmountable: “the great difference between man and monkey is in the larynx, he continued,—in the incapacity to frame delicately different sound-symbols by which thought could be sustained.” In his attempts to bridge that gap and become a god, Moreau tortures animals in his “House of Pain” with his unique surgeries, and feels no compunction for doing so: “it is just this question of pain that parts us. So long as visible or audible pain turns you sick; so long as your own pains drive you; so long as pain underlies your propositions about sin,—so long, I tell you, you are an animal, thinking a little less obscurely what an animal feels.” Moreau’s amorality is almost without precedent in literature, but may echo Wells’ reading of Nietzsche, even as it seems to pre-empt Freud: “Very much indeed of what we call moral education, he said, is such an artificial modification and perversion of instinct; pugnacity is trained into courageous self-sacrifice, and suppressed sexuality into religious emotion.” (Moreau, Chapter 14).

The darkness of the novel is defined not so much by Moreau’s attitudes and deeds as by the fact he often appears the sanest and most intelligent presence in the novel, and by the fact Prendick becomes haunted by the sense there is something human, after all, in the beings Moreau has created or recreated:

I cannot explain the fact,—but now, seeing the creature there in a perfectly animal attitude, with the light gleaming in its eyes and its imperfectly human face distorted with terror, I realised again the fact of its humanity. In another moment other of its pursuers would see it, and it would be overpowered and captured, to experience once more the horrible tortures of the enclosure. Abruptly I slipped out my revolver, aimed between its terror-struck eyes, and fired.

A strange persuasion came upon me, that, save for the grossness of the line, the grotesqueness of the forms, I had here before me the whole balance of human life in miniature, the whole interplay of instinct, reason, and fate in its simplest form.

Moreau, Chapter 16

This is the ultimate shock to Prendick’s sense of an ordered human existence in a benevolent universe:

I must confess that I lost faith in the sanity of the world when I saw it suffering the painful disorder of this island. A blind Fate, a vast pitiless mechanism, seemed to cut and shape the fabric of existence and I, Moreau (by his passion for research), Montgomery (by his passion for drink), the Beast People with their instincts and mental restrictions, were torn and crushed, ruthlessly, inevitably, amid the infinite complexity of its incessant wheels.

Moreau, Chapter 16

Though the Beast People appear at times more people than beasts, their lives and deaths are treated by Prendick – not to mention Moreau – with the utmost casualness. Prendick is sometimes disturbed by their humanity, but more often hates them violently. His questioning of the nature of humanity when he sees the Beast People has a perhaps even darker echo in an almost contemporaneous work, Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad. Marlow is never so disturbed in that work as when he acknowledges his kinship with those he calls savages:

They howled and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity—like yours—the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar. Ugly. Yes, it was ugly enough; but if you were man enough you would admit to yourself that there was in you just the faintest trace of a response to the terrible frankness of that noise, a dim suspicion of there being a meaning in it which you—you so remote from the night of first ages—could comprehend.

HoD, II

There are numerous points of similarity between HoD and Moreau. HoD is obviously about colonialism but is also a reflection on what it means to be human or bestial, civilized or savage; Moreau is obviously about the line between humanity and bestiality but is also a sort of reflection on the colonialist mentality. They are like two sides of the same coin. Take the very similar passages near the ends of both, when the protagonists return from their sojourns in hell, and find London itself has taken on a nightmarish complexion, its inhabitants not as unproblematically human as they seemed before:

When I lived in London the horror was well-nigh insupportable. I could not get away from men: their voices came through windows; locked doors were flimsy safeguards. I would go out into the streets to fight with my delusion, and prowling women would mew after me; furtive, craving men glance jealously at me; weary, pale workers go coughing by me with tired eyes and eager paces, like wounded deer dripping blood; old people, bent and dull, pass murmuring to themselves; and, all unheeding, a ragged tail of gibing children.

Moreau, Chapter 22

I found myself back in the sepulchral city resenting the sight of people hurrying through the streets to filch a little money from each other, to devour their infamous cookery, to gulp their unwholesome beer, to dream their insignificant and silly dreams. They trespassed upon my thoughts. They were intruders whose knowledge of life was to me an irritating pretence, because I felt so sure they could not possibly know the things I knew. Their bearing, which was simply the bearing of commonplace individuals going about their business in the assurance of perfect safety, was offensive to me like the outrageous flauntings of folly in the face of a danger it is unable to comprehend. I had no particular desire to enlighten them, but I had some difficulty in restraining myself from laughing in their faces so full of stupid importance.

HoD, III

It is no accident. Conrad was an admirer of Wells and dedicated his novel The Secret Agent to him. He also called him “a very original writer with a very individualistic judgment in all things and an astonishing imagination” (Jocelyn Baines, Joseph Conrad: A Critical Biography, Penguin, 1986, p.282). Wells seems on the whole less impressed by Conrad and described their relation as “a long, fairly friendly but always rather strained acquaintance” (op. cit., p. 284). Later, he took a few rather petty potshots at Conrad in the novel Boon (1915) and they became estranged.

Still, reflecting on the works together is intriguing. There is no doubt Conrad had read Wells’ book before writing HoD and to see Moreau as a forerunner of Kurtz is tempting: the white man in the jungle with ultimate power over the savage indigenous life, power that makes him mad, turns his genius into amorality and brings into question the nature of humanity. Both are megalomaniacal. Moreau insists he is following “the Maker of this world”; Kurtz goes further and explicitly identifies with godlike powers:

He began with the argument that we whites, from the point of development we had arrived at, ‘must necessarily appear to them [savages] in the nature of supernatural beings—we approach them with the might of a deity,’ and so on, and so on.

HoD, II – square brackets as in original.

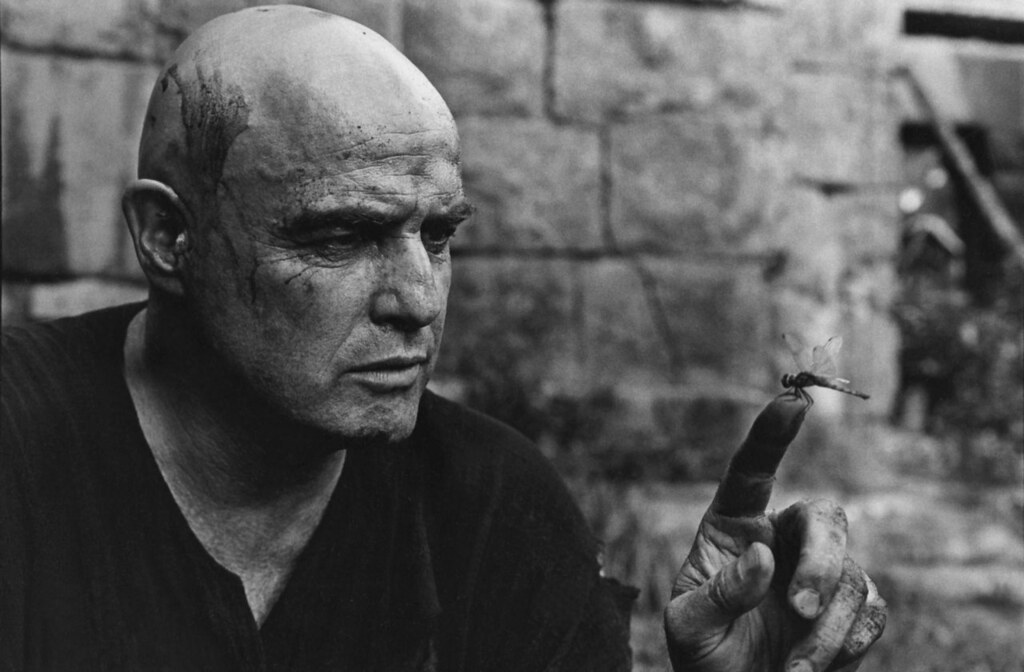

A nice indication that Kurtz and Moreau were, in a sense, the same character is that Marlon Brando famously played Kurtz in Apocalypse Now (1979) and, some years later, played Moreau in the much-maligned adaptation The Island of Dr. Moreau (1993). It is unsurprising a figure of Brandon’s stature seemed needed for these Übermenschen, even if his success was mixed in bringing them to life.

Conrad read Wells and perhaps the central scenario of Moreau was filtered through Conrad’s own memory of the Congo, allowing him a new manner of seeing the brutality and hubris of the colonising mission and resulting in the classic Heart of Darkness. At the denouement, though, Conrad’s Marlow embraces the lie. Wells never does that, and his work is perhaps the more uncompromising. I cannot deny it is my favourite of the two, a dissection as cold and merciless as anything Moreau got up to in his “House of Pain”.