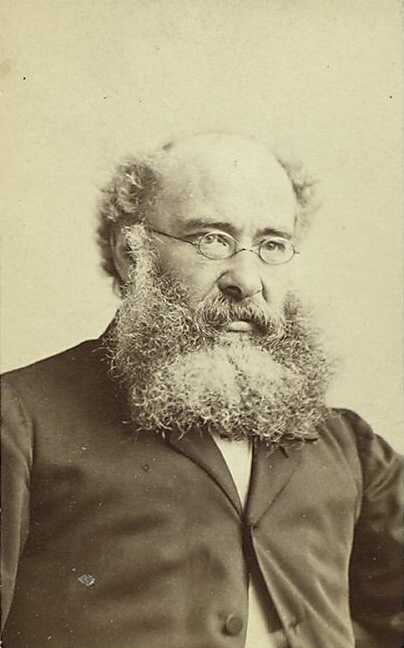

Anthony Trollope: The Rich Man’s Dickens

by Mark Wallace

I’ve read several Trollope novels over the years, but never ended one with the urge to go on a binge of his ouevre. A recent reading of Barchester Towers (1867), one of his best-known novels, reminded me of his limitations.

Trollope has always tended to divide opinion. One of the most oft-cited critical essays on him came from Henry James in 1883, a few months after Trollope’s death. James opens up with a judgment on Trollope’s quality as a litterateur:

The author of The Warden, of Barchester Towers, of Framley Parsonage, does not, to our mind, stand on the very same level as Dickens, Thackeray and George Eliot; for his talent was of a quality less fine than theirs. But he belonged to the same family—he had as much to tell us about English life; he was strong, genial and abundant.

Anthony Trollope: The Critical Heritage, ed. Donald Smalley, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969 p. 535.

(also here: https://victorianweb.org/authors/jamesh/trollope.html)

This is a conversation that still follows Trollope around: a good novelist, certainly, but perhaps not quite a great one. On the 200th anniversary of Trollope’s birth, The Guardian ran an article including various eminent persons’ choices for his best novel. The article opened with the rhetorical but revealing question: “Poor man’s Dickens, or master of motives and manners?” Whatever about a master of motives and manners, Trollope was not a poor man’s anything. Poverty was not one of his major concerns as a novelist.

Barchester Towers opens with the chapter title “Who will be the new Bishop?“ This chapter title tells us a lot about Trollope, his priorities and the questions that interest him. The chapter opens with the death of Dr. Grantly, otherwise Bishop Grantly; his son, Archdeacon Grantly, otherwise Dr. Grantly (yes, as well), is the favourite for the position. “The prime minister”, the narrator notes, his given the Archdeacon reason to believe the position is his. He has given no firm assurance but, the narrator says:

those who know anything either of high or low government places will be well aware that a promise may be made without positive words

Barchester Towers, Barnes & Noble, 2005 [1857], p. 10

This is a rather narrow and alienating reference. What of those unfamiliar with high or low government places? Why are they absent from Trollope’s consideration? Yet the reference is indicative of the book’s frame of reference because in the opening few pages we are introduced to a host of titled persons and very few untitled. The narrator also uses various references to prime ministers, ministries and cabinets in these pages to create the impression of inside knowledge of the world of politics and positions. The casual reference to knowledge of “high or low government” places is a typical Trollopian device to situate his narrator in the place of knowledge of and casual access to worldly and elitist things.

As to the death that takes place in these early pages, Trollope is unsentimental about it:

The archdeacon’s mind, however, had already travelled from the death chamber to the closet of the prime minister. He had brought himself to pray for his father’s life, but now that that life was done, minutes were too precious to be lost. It was now useless to dally with the fact of the bishop’s death—useless to lose perhaps everything for the pretence of a foolish sentiment.

Barchester, p. 13

Trollope is unjudgmental about his character’s lack of sentiment. The archdeacon is not intended as an unlikeable figure. Obviously in this treatment of death, he differs markedly from Dickens. Death is always momentous for Dickens, while for Trollope it is an opening of a new position for somebody or other.

Trollope gives great detail about the bishopric in question, particularly financial. Of the archdeacon he notes:

His preferment brought him in nearly three thousand a year. The bishopric, as cut down by the Ecclesiastical Commission, was only five. He would be a richer man as archdeacon than he could be as bishop.

Barchester, p. 17

Archdeacon Grantly is not motivated by money, then, but by power and position. Trollope, however, is conscious of both. He cannot mention a position without also specifying the wages thereof. We know not only the salary that goes with the bishopric, but that of all the positions associated with Barchester Hospital:

it had been ordained that there should be, as heretofore, twelve old men in Barchester Hospital, each with 1s. 4d. a day; that there should also be twelve old women to be located in a house to be built, each with 1s. 2d. a day; that there should be a matron, with a house and £70 a year; a steward with £150 a year; and latterly, a warden with £450 a year, who should have the spiritual guidance of both establishments, and the temporal guidance of that appertaining to the male sex.

Barchester, p. 21

Such detail is eminently Trollopian. One of his USPs among the Victorian literary world was his familiarity, which he accentuated whenever possible, with matters financial and professional. Here, clearly, was a man of the world, and proud of it. But not all men and women in the world are of the world in the Trollopian sense, and this wealth of detail comes at the expense of narrowing the author’s sphere of interest and sympathy. These details can also not fail to lose their interest for posterity’s reader, much as they may have been relevant to Trollope’s contemporaries.

A curious habit of Trollope’s was heavily criticised by James in the 1883 essay:

He took a suicidal satisfaction in reminding the reader that the story he was telling was only, after all, make-believe.

Critical Heritage, p. 535

In Barchester Towers Trollope not only makes reference to his story being a story, but also uses the related but somewhat inconsistent technique of repeatedly stressing his own honesty. He is very fond of formulations like “in truth”. In chapter 4, while introducing the character Obadiah Slope, Trollope includes two instances of “in truth” and one “to tell the truth” within half a page. In chapter 1, he asks a rhetorical question and answers himself: “No, history and truth compel him to deny it.” Yet he is also fond, as in an example used by James, of insisting on the made-up quality of his story:

The end of a novel, like the end of a children’s dinner party, must be made up of sweetmeats and sugar-plums.

Barchester, P. 507

Both of these techniques appear throughout Barchester Towers. They are each forms in which Trollope draws attention to himself as author. One demonstrates his honesty and fair-mindedness and the other reminds the reader of who is the guiding intelligence in the situation. Trollope delights in drawing attention to himself as a writer and, done too regularly, this can create a sense of a rather self-satisfied person.

Self-satisfied is a term that seems fitting for Trollope. He is happy with the status quo in society and with his personal status quo as a popular writer. He dislikes those who try to move above their station. Consider the one truly vituperative portrayal in Barchester Towers, that of Obadiah Slope. Trollope’s very first observation of Slope is:

Of the Rev. Mr. Slope’s parentage I am not able to say much.

Barchester, p. 28.

Slope wants to upend church tradition and to rise from humble beginnings, and Trollope uses every rhetorical tool in his arsenal to discredit these goals. The portrait and its lack of balance is revealing of Trollope’s general outlook, one of comfortable indulgence towards all who do not rock the boat, and suspicion of those who threaten to interfere with the established order.

The Guardian asked if he was a poor man’s Dickens, but Dickens was more of a poor man’s Dickens than Trollope. A poor man, unless he had some immediate hopes of advancement, would learn little of relevance to his life from Trollope. Trollope was the wealthy man’s – or at least the comfortably-off man’s – Dickens.