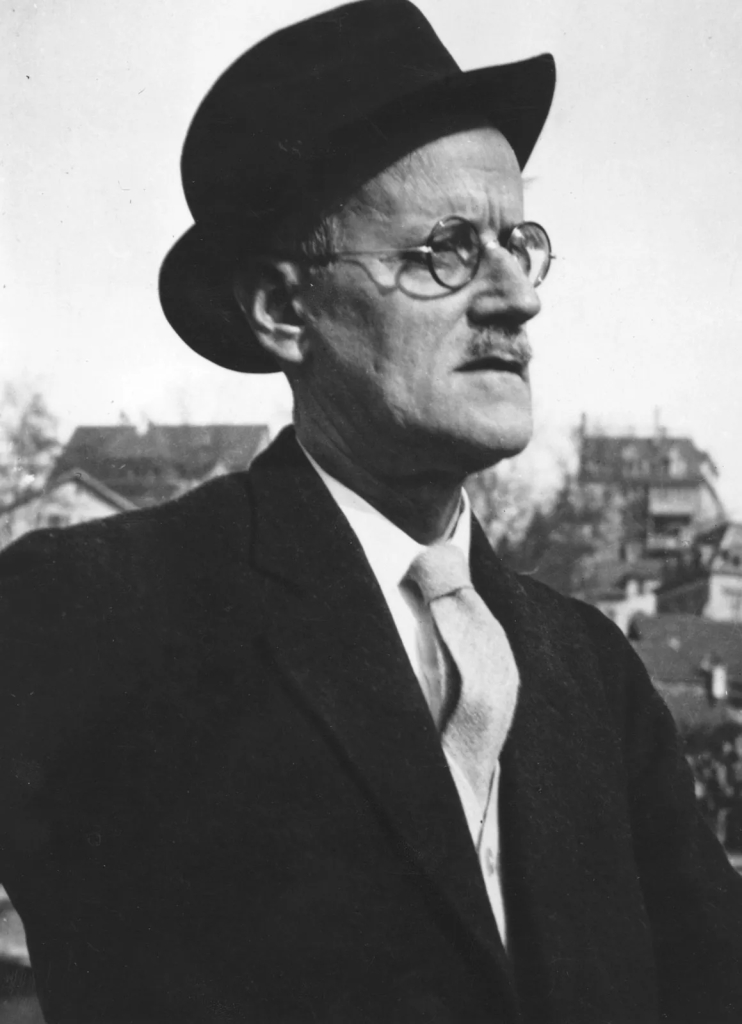

Gerty in Ulysses: James Joyce’s Farewell to Narrative

by Mark Wallace

The difficulties presented by James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) are notorious but they are not uniform throughout the book. With each of the 18 chapters or “episodes” written in a very different style, some are surprisingly straightforward and others are essentially impenetrable on first reading. Occasionally, dare one say it, there is an episode that is quite enjoyable for the first-time reader.

It is often stated that, in general, the book gets more obscure as it goes on, with some of the most unbearable challenging episodes coming late on (most notably Nos. 14 and 15, “Oxen of the Sun” and “Circe”). These later episodes anticipate Joyce’s final novel, Finnegans Wake (1939), a novel so difficult that critics can’t agree whether it has a narrative or should even be classed as a novel.

But just before Joyce went over the edge one final time into language games, multilingual punning and torturing the reader, he produced one of his great feats of straightforward storytelling, Ulysses episode 13, “Nausicaa”, centred on Gerty MacDowell, a character almost entirely absent from the rest of the book. “Nausicaa” is a reminder of the Joyce of Dubliners (1914) and much of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), a storyteller of precision and clarity, one who had brought the art of narrative to such a pitch of perfection that now he had nowhere left to go but into anti-narrative.

“Nausicaa” opens:

The summer evening had begun to fold the world in its mysterious embrace. Far away in the west the sun was setting and the last glow of all too fleeting day lingered lovingly on sea and strand, on the proud promontory of dear old Howth guarding as ever the waters of the bay, on the weedgrown rocks along Sandymount shore and, last but not least, on the quiet church whence there streamed forth at times upon the stillness the voice of prayer to her who is in her pure radiance a beacon ever to the stormtossed heart of man, Mary, star of the sea..

It is a nice and very clear piece of scene-setting. We know where we are, Sandymount strand; when it is, a summer evening; and at least one thing that is happening, a Catholic prayer ceremony in the nearby church. There is some nice alliteration: “lingered loving on sea and strand, on the proud promontory” and a nod towards Joyce’s neological leanings with “weedgrown”. Amidst all the unwonted clarity, there is some very curious phrasing. Why is Howth “dear old Howth”? Why is the evening said to have a “mysterious embrace”? Is Mary really “in her pure radiance a beacon ever to the the stormtossed heart of man”? Such observations are rather trite and clichéd. There is an element of parody, of Joyce pretending to be a more derivative and conventional writer than he is. Yet in the context of Ulysses, the very triteness of these lines is in itself intriguing and compelling.

Gerty, we soon discover, is a young lady of about 20, and is passing the evening with two girl friends, one of whom is looking after her younger siblings:

Gerty MacDowell who was seated near her companions, lost in thought, gazing far away into the distance was, in very truth, as fair a specimen of winsome Irish girlhood as one could wish to see. She was pronounced beautiful by all who knew her though, as folks often said, she was more a Giltrap than a MacDowell. Her figure was slight and graceful, inclining even to fragility but those iron jelloids she had been taking of late had done her a world of good much better than the Widow Welch’s female pills and she was much better of those discharges she used to get and that tired feeling.

Again the reliance on cliché is apparent. First, Joyce backs up his own description with “in very truth”, always a meaningless statement for the narrator of a fiction to make. That Gerty is “as fair a specimen of winsome Irish girlhood as one could wish to see” is the epitome of romantic banality, recalling magazine literature of the time. Yet in the next line any sense of romance is quickly undercut, first by the reference to her being “more a Giltrap than a MacDowell”, which rings true as a realistic commonplace observation but not as a component of romantic literature. More jarring is the prosaic reference to “iron jelloids”, an everyday touch like those found in profusion throughout Ulysses. Even more typical is the reference to Gerty’s “discharges”, a vulgar usage by the time’s standards but in keeping with the obsession with bodily functions throughout the novel. The episode is already performing a delicate balancing act between being a pastiche or parody of romantic literature and being a realistic window into the consciousness of a young middle-class Dublin woman, including the indelicate bits normally left unspoken by novels in the romantic or any other genre.

In fact, “Nausicaa” was the straw that broke the camel’s back and led to the publishers of Ulysses in instalments being prosecuted and fined in the USA. It was the first chapter of the book to be seen from a female perspective (the famous Molly Bloom soliloquy not appearing until the final chapter), and detailed descriptions of underclothes and bodily functions, which had been just about acceptable in a male context, caused grave offence when relating to a woman.

Joyce lays it on thick in the parodic tributes to Gerty’s youthful fairness: “God’s fair land of Ireland did not hold her equal”; “a joyous little laugh which had in it all the freshness of a young May morning.” Like her looks, Gerry’s consciousness is constituted of romantic cliché:

No prince charming is her beau ideal to lay a rare and wondrous love at her feet but rather a manly man with a strong quiet face who had not found his ideal, perhaps his hair slightly flecked with grey, and who would understand, take her in his sheltering arms, strain her to him in all the strength of his deep passionate nature and comfort her with a long long kiss. It would be like heaven.

It is all notably Mills and Boon (founded in 1908 so perhaps Joyce was familiar) but what in the context of a Mills and Boon novel might be risible, in the context of Ulysses is remarkably effective because, having read through to this point, we have a sense of the keen literary intelligence behind the clichés. There is also an effective contrast between the obsessively romantic workings of Gerty’s mind and the prosaic surroundings which often intrude, from squabbling children to iron jelloids.

Gerty experiences her life as a romantic story and is almost a female Don Quijote, a person so deeply embedded in the imaginative universe created by generic literature that it transfigures her life and makes her potentially sordid encounter with Bloom read as a moment of true ecstasy for both. The true ironic tension in the episode is between romance and sordidness, Joyce proving himself equally adept at striking either note though, as often in Ulysses, seeming to finally settle on the latter.

Gerry encounters Bloom as the episode wears on, and the two are mutually impressed. He is “the image of the photo she had of Martin Harvey, the matinee idol, only for the moustache”; she, to him, is ” a fair unsullied soul”. They do not address each other but their eyes meet across the strand as Bloom is briefly engaged in conversation by one of Gerty’s friends and the effect on both is profound and profoundly satisfying. Gerty deliberately provides Bloom a glimpse of her underwear; he pleasures himself discreetly as he looks on. A sort of climax ensues, certainly sexual for him, of an unspecified type for her. For Bloom this is followed by the somewhat bathetic discovery that Gerty is lame, which is also a surprise to the reader. Only now, when we see through Bloom’s eyes as she limps away up the strand, do we gain this insight into her situation. Throughout Gerty’s own reflections and romantic fantasies, she has never clearly alluded to this complicating factor. Bloom considers it a shame but classes Gerty as a “Hot little devil all the same”.

As the episode winds to a close, we leave Gerty behind and find ourselves once again trapped in the consciousness of Bloom, a place of obscurity and without grammar:

Wait. Hm. Hm. Yes. That’s her perfume. Why she waved her hand. I leave you this to think of me when I’m far away on the pillow. What is it? Heliotrope? No. Hyacinth? Hm. Roses, I think. She’d like scent of that kind. Sweet and cheap: soon sour. Why Molly likes opoponax. Suits her, with a little jessamine mixed. Her high notes and her low notes. At the dance night she met him, dance of the hours. Heat brought it out. She was wearing her black and it had the perfume of the time before. Good conductor, is it? Or bad? Light too. Suppose there’s some connection. For instance if you go into a cellar where it’s dark. Mysterious thing too. Why did I smell it only now? Took its time in coming like herself, slow but sure. Suppose it’s ever so many millions of tiny grains blown across. Yes, it is. Because those spice islands, Cinghalese this morning, smell them leagues off. Tell you what it is. It’s like a fine fine veil or web they have all over the skin, fine like what do you call it gossamer, and they’re always spinning it out of them, fine as anything, like rainbow colours without knowing it. Clings to everything she takes off. Vamp of her stockings. Warm shoe. Stays. Drawers: little kick, taking them off. Byby till next time. Also the cat likes to sniff in her shift on the bed. Know her smell in a thousand. Bathwater too. Reminds me of strawberries and cream. Wonder where it is really. There or the armpits or under the neck. Because you get it out of all holes and corners. Hyacinth perfume made of oil of ether or something. Muskrat. Bag under their tails. One grain pour off odour for years. Dogs at each other behind. Good evening. Evening. How do you sniff? Hm. Hm. Very well, thank you. Animals go by that. Yes now, look at it that way. We’re the same. Some women, instance, warn you off when they have their period. Come near. Then get a hogo you could hang your hat on. Like what? Potted herrings gone stale or. Boof! Please keep off the grass..

The irony is that Gerty’s consciousness, given over to reproducing the romantic life she has read about and with scarce room for anything else, is far more amenable to the reader than Bloom’s wide-ranging and capacious thoughts on life, the universe and everything. Her consciousness is cohesive and – though clichéd – literary, while Bloom’s is fragmented. Reading “Nausicaa” gives us a better idea than any other piece of text of the two Joyces: the brilliant narrative artist, brilliant even when he is trying to be trite, and the pioneering chronicler of modern consciousness. The originality of the latter approach cannot be denied, but much was lost, too, when Joyce ceased to find interest in the telling of stories. There is a tension in Joyce’s work between narrative and consciousness; in delineating the latter, he evicted the former. For many put-upon readers of Ulysses, “Nausicaa” may instil a suspicion that the sacrifice was greater than the gain.