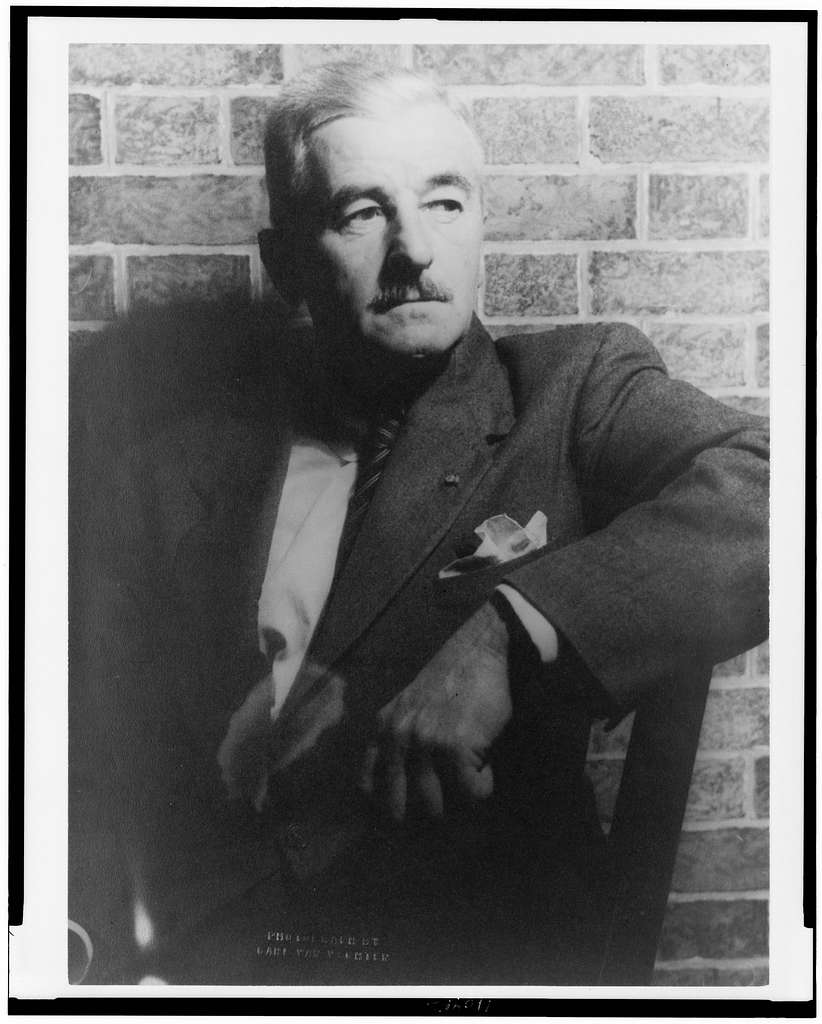

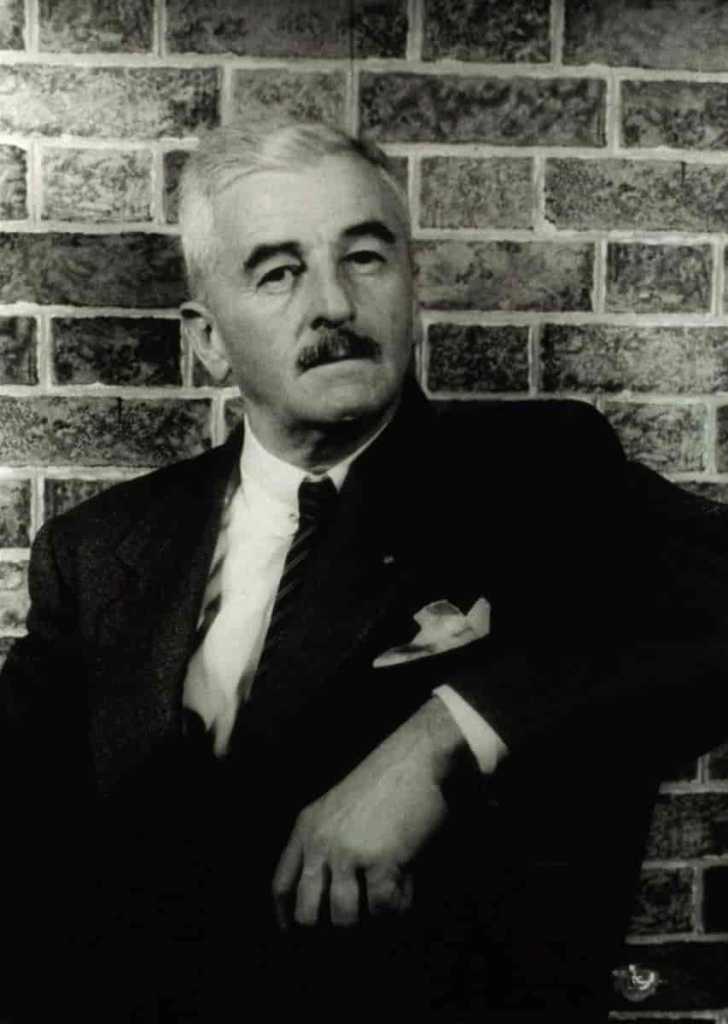

Joe Christmas: Dickensian Orphan, Christlike Saviour and Conradian Racial Symbol in William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932)

by Mark Wallace

The opening pages of William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932) include an indictment of industrial ruin that resonates more strongly today than on its publication:

All the men in the village worked in the mill or for it. It was cutting pine. It had been there seven years and in seven years more it would destroy all the timber within its reach. Then some of the machinery and most of the men who ran it and existed because of and for it would be loaded onto freight cars and moved away. But some of the machinery would be left, since new pieces could always be bought on the instalment plan – gaunt, staring, motionless wheels rising from mounds of brick rubble and ragged weeds with a quality profoundly astonishing, and gutted boilers lifting their rusting and unsmoking stacks with an air stubborn, baffled and bemused upon a stumppocked scene of profound and peaceful desolation, unplowed untilled, gutting slowly into red and choked ravines beneath the long quiet rains of autumn and the galloping fury of vernal equinoxes.

William Faulkner, Light in August, Vintage, 1990, p. 4

This graveyard of machinery recalls that found near the infamous “grove of death” by Marlow in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness:

I came upon a boiler wallowing in the grass, then found a path leading up the hill. It turned aside for the boulders, and also for an undersized railway-truck lying there on its back with its wheels in the air. One was off. The thing looked as dead as the carcass of some animal. I came upon more pieces of decaying machinery, a stack of rusty rails.

Heart of Darkness

In Conrad’s book, wilderness has already begun to reclaim the jungle despite industrialism’s best efforts. Faulkner, perhaps informed by Conrad, is imagining such a future for his patch of the American south. It is not the only thing these two novels have in common. Faulkner was cagey about being influenced by Conrad when asked during an interview at the University of Virginia, but admitted to reading some of his work repeatedly. Conrad was, of all canonical writers before Faulkner, the one most obsessed with race, constantly ascribing a symbolical importance to it, most notably in the less read The Nigger of the “Narcissus“, which Faulkner significantly names in the Virginia interview as the Conrad novel he repeatedly returns to. I have already written about the symbolical use of blackness in that novel.

In Light in August, Faulkner manages to provide an even more complex rumination on the idea of blackness. The masterstroke in the novel, rendering it endlessly ambiguous and unsettling, is that the central character Joe Christmas is never confirmed as being part black, but, an orphan of unknown parentage, he believes he is and is endlessly obsessed by the notion. Visually, he can pass for white, but as a young child he is moved from the white orphanage to the black one when a nurse who wants to get him out of the way because he has seen her engaging in an illicit affair with a colleague convinces the matron he has “negro” blood. This changes Joe Christmas’ life and is his primal scene, setting up the hatred of sex, hostility to women and racial guilt that will shape his adult life.

Further complicating this character is the parallel to Jesus Christ throughout. The name Joe Christmas recalls Christ both in the surname and in the initials JC. He was born at Christmas and dies at 33. The parallel seems both devout and blasphemous.

The name Joe Christmas is not a birth name. He is given it at the orphanage because of the time of year when he is found. This act of naming evokes a parallel to Oliver Twist, named by the beadle in the orphanage at the beginning Oliver Twist in line with his own nomenclatural formula, and Joe’s life course seems a dark commentary on the peregrinations of a Dickensian orphan. He is perhaps closer to Bleak House‘s Jo than to Oliver and, apart from the racial element, might almost be an answer to the question of what would have happened to Jo if he had outlived that bout of smallpox. Recall Jo’s ignorance of religion and so on before the inquest:

Name, Jo. Nothing else that he knows on. Don’t know that everybody has two names. Never heerd of sich a think. Don’t know that Jo is short for a longer name. Thinks it long enough for HIM. HE don’t find no fault with it. Spell it? No. HE can’t spell it. No father, no mother, no friends. Never been to school. What’s home? Knows a broom’s a broom, and knows it’s wicked to tell a lie. Don’t recollect who told him about the broom or about the lie, but knows both. Can’t exactly say what’ll be done to him arter he’s dead if he tells a lie to the gentlemen here, but believes it’ll be something wery bad to punish him, and serve him right—and so he’ll tell the truth.

Bleak House, Chapter XI

Perhaps it is from Dickens’ Jo that Faulkner found inspiration for his first name. Certainly, in the aforementioned Virginia interview, he mentioned “most of Dickens” as being among the books he read as a youth which he “set [his] store by”. Joe and Jo are linked by their remarkable ignorance of concepts we consider essential parts of our psychological make-up. This ignorance serves to defamiliarise the concepts for the reader. Reading Jo’s reflections on God, the afterlife and sin force to reader – and more pointedly forced the Victorian reader – to reflect on those concepts anew, from the point of view of one living in that society and oppressed by it yet in one sense free from its ruling ideological concepts.

In the memorable flashback section detailing Joe Christmas’s childhood there is a similar sense of a human being too young and too neglected to understand basic human ideals and emotions, which also suggests the constructedness of such emotions: “He didn’t know that she was crying because he did not know that grown people cried[…]” (136) The exception might be guilt. Guilt, it seems, is primal, even when you don’t know what you feel guilty of: “Perhaps he expected to be punished upon his return, for what, what crime exactly, he did not expect to know, since he had already learned that, though children can accept adults as adults, adults can never accept children as anything but adults too.” (140) Like a Dickensian orphan, he is a perfect victim. Like Jo, he knows nothing of religion: “He had neither ever worked nor feared God. He knew less about God than about work.”(144) It is all the more discomfiting and ambiguous, then, to discover the Christian echoes in Joe’s later life and death. Though in many ways the opposite of Christlike, there is yet some suggestion that Joe willingly takes the sins of the American South on himself and that his death, somehow, has a redemptive quality.

Light in August is a mysterious book and Joe Christmas cannot be explained neatly. The book is more complex than that, too, because his story is interwoven with the tangentially linked tales of Lena and Hightower. Hightower, like Joe but in a very different way, is tortured by the history of the American South. Lena is a paragon of bovine sanctity, incapable of self-reflection and perhaps an indication that Faulkner, who could do so much, struggled to create sympathetically complex female characters. Her simplicity is almost akin to that of the derided Dickensian heroines. At least she serves, as a young pregnant woman who loves life beyond reason, to illustrate that, if Joe must die, life goes on in its way. She allows one to argue that Light in August is an optimistic novel. Like much of Dickens again, though, it strength is not in its positivity or its light but in its darkness.